In a time before it was ironic to have a magazine called "Crack Comics," Quality Comics published this book, and the similar "Smash Comics." While Smash Comics starred mainly a Spirit lookalike called Midnight, and an oversized robot called Bozo the Iron Man, the main draw for Crack Comics was Captain Triumph.

Captain Triumph was sort of a Golden Age precursor to DC's Firestorm in that Lance Gallant had a ghostly twin brother with whom he communicated. When Lance rubbed the strange birthmark on his wrist he merged with the spirit of his brother Michael to form Captain Triumph. Captain Triumph was super-strong, fairly invulnerable, and his only weakness seemed to be that Lance Gallant was

As the splash page proclaims: "Lance Gallant calls forth the spirit of his dead twin brother, Michael, to form the indomitable Captain Triumph."

In this story, Lance, along with his comrades Biff and Kim, encounter a con-man named Silvertip, who poses as a mystic in order to rob the rich. Once Captain Triumph appears the balance of power is strongly in his favor. At one point the desperate Silvertip threatens to commit suicide as his only option to escape Captain Triumph.

11/27/11

11/21/11

"Supergods" by Grant Morrison

Grant Morrison, one of the top writers for DC in the 21st Century, believes in Super Heroes, both real and imagined. He explores the existence of these heroes in his book "Supergods." Subtitled "What masked vigilantes, miraculous mutants, and a sun god from Smallville can teach us about being human," the inside flap claims that "Morrison draws on art, science, mythology, and his own astonishing journeys through this shadow universe to provide the first true history of the superhero." As I read deeper into the book, I began to wonder if this statement had a dual meaning in Mr. Morrison’s mind.

The book begins innocently enough. The first of four sections, "The Golden Age" roughly corresponds to the comic book industry’s acknowledged golden age from 1938 until the decline of superheroes in the early ‘50s, the publication of Frederck Wertham’s "Seduction of the Innocent," and the advent of the Comics Code.

The Silver Age section starts with an analysis of Mort Weisinger’s Superman stories from the late ‘50s and coasts into the early ‘70s with Jack Kirby’s creations of OMAC and the New Gods, and Marvel Comics’ Captain Marvel and other psychic/psychedelic comics.

The Dark Age starts in the early ‘70s, touching on the Green Lantern/Green Arrow team-up when it’s discovered that Speedy is a drug addict, and then caroming off Frank Miller’s "The Dark Knight Returns," Alan Moore’s "The Watchmen," and Morrison’s own "Zenith," until bouncing once or twice off Image and Vertigo imprints and dropping into the depths somewhere around the year 2000.

The fourth section, comprising over 150 pages -- over a third of the book -- concerns the time period from 2000 until the present, an era that Morrison considers The Renaissance.

"Supergods" is marketed as a history of comics, and an analysis of the heroes, but the book actually follows two threads. After the Golden Age, we find Morrison mapping his autobiography onto the history of comics, showing how the comics have influenced his life, and how he in turn has influenced comics.

The psychoanalyses of the characters in the Golden Age are interesting, but read a bit too quickly, as if Morrison is reciting what he’s learned without having lived it. And it’s true. Born in the ‘60s, he may have read the Golden Age comics, but through a filter of a more modern time. Evidently he feels the same way, since only about 50 pages are devoted toward establishing the tropes from the birth era of the superheroes.

In the Silver Age, Morrison starts to weave his personal history into the comics, clearly expressing a preference for The Flash and DC’s "multiverse." At this point we begin to see glimpses of Morrison’s obsession: "If Barry [Allen, the Flash] lived on a world where Jay [Garrick, The Flash of Earth-2] was fictional, did that mean we, as readers, were also part of Schwartz’s elegant multiversal architecture?" For a full chapter he continues to explore how the existence of multiple universes has manifested itself to us, both in the comics and in the "real" world. He cites "cosmologists" who say that the multiverse is real, and then a few paragraphs later talks about the emergence of continuity in comics "first recognized by Gardner Fox, Julius Schwartz, and Stan Lee as a kind of imaginative real estate that would turn mere comic books into chronicles of alternate histories.

This chapter, "Infinite Earths," examines many of the key ideas that have captured Morrison’s attention, including the possibility of having real superheroes. "In so many ways, we’re already superhuman. Being extraordinary is so much a part of our heritage as human beings that we often overlook what we’ve done and how very unique it all is." He also considers what other dimensions might exist. "Superhero science has taught me this: Entire universes fit comfortably inside our skulls. Not just one or two but endless universes can be packed into that dark, wet, and bony hollow without breaking it open from the inside…To find out what higher dimensions might look like, all we have to do is study the relationship between our 3-D world and the 2-D comics. A 4-D creature could look ‘down’ on us through our wall, or clothes, even our skeletons…perhaps even our thoughts."

And then Morrison takes the biggest leap. He describes how he asked an artist to create a comic-book avatar of himself so that he might don this "fiction suit" and enter the comic-book work. At first I thought maybe this was some sort of mental writer’s exercise, but he describes being immersed so completely in the comic that it’s almost an altered state of consciousness. He describes how, while working on his comic "The Invisibles," he found characters actively resisting his will. "Perhaps, like a beehive or a sponge colony, I’d put enough information into my model world to trigger emergent complexity…I wondered if ficto-scientists of the future might finally locate this theoretical point where a story becomes sufficiently complex to being its own form of calculation and even become in some way self-aware…I imagined a sentient paper universe and decided I would try to contact it."

The Dark Age of superheroes concentrates mostly on "Batman: The Dark Knight Returns," and "Watchmen," which could be considered two of the most influential graphic novels of all time, but isn’t it perhaps irrelevant to mention such massive influences to the current generation? Morrison doesn’t do much to put these in context, except to exclaim that they are the context. Still, I appreciate his short survey of punk British comics that were also taking the stage, such as "Tank Girl" by Jamie Hewlett and Alan Martin, Pat Mills’ "Marshall Law," and "Enigma" by Peter Milligan and Duncan Fegredo. The most interesting part of the Dark Age section is how it corresponds to Morrison’s own life. Up until his late 20’s he claims to have been straight-edged, but he suddenly starts exploring alcohol, mushrooms and other mind-altering drugs. Flush with cash from his best-selling book "Arkham Asylum," and filling out his monthly income by writing a couple hundred pages a year, he begins to binge-travel and perform magical experiments. Reading about cross-dressing berdache shamans, he adopts a female alter-ego for some of the darker magical operations. At the end of the section Morrison describes a mystical experience which becomes a turning point in his life.

Curiously, the incident of Morrison’s mystical experience in Kathmandu ends the Dark Age, but also begins the Renaissance. He explains that while partying in Nepal, he begins to lose contact with the physical reality of his hotel room. The walls dissolve into ancient streets and archaic half-remembered dreams of childhood. He feels "presences" emerging from the surroundings, described as blobs of pure holographic meta material, or chrome angels, he intuits they may have come from Alpha Centauri. They lead him to their galaxy, where he accidentally offends the locals and is then given "The secret of the universe." This secret is something about how to "plug into" the information lattices of reality.

After his otherworldly vision, however, Morrison goes into a decline, locking himself away in his house, and eventually being checked into the hospital. What he describes as "boils, traditional sign of demon contact," the doctor cures with antibiotics. Even now Morrison can’t reconcile his experience. "What’s important about this experience is not whether there are ‘real’ aliens from a fifth-dimension heaven where everything is great and we’re all friends. There may well be, but I have no real proof."

I found that after this revelation the book began to meander as closed in on present day. The details are clearer, but the stories have less passion. The survey of superhero movies is about as constructive as a couple hours spent browsing the internet -- search phrase: "comic book movies." Similarly, his props for writers and artists at DC and Marvel in the first decade of the 21st century are admirable, but lack the context they will be given by history. The most interesting arc is his description of DC’s "Crisis" trilogy, which includes his own "Final Crisis." It’s also interesting to see how he waves off the "event fatigue" in comics in the new century, while failing to mention that it is problem caused primarily by the publishers, who saw such success and excess in the 1990’s that they are continuing to create hype rather than craft stories.

As comic history book go, Supergods is far from ideal. As mentioned, the Golden Age essays are only average. The illustrations are all only from DC Comics, which is the publisher that Morrison currently works with. Also, Morrison plays with time, to such a degree that it’s disturbing to someone who might rely on this book as history. For example, he juxtaposes the movie "The Dark Knight," which was released in 2008, with the events of September 11th, 2001, as if the movie somehow preceded the terrorist attacks. There are multiple other examples where events that may have been years apart, Morrison brings together for dramatic effect. And finally, if you’re looking for an objective account, look elsewhere. Morrison’s ego is not small, and he’s constantly infiltrating himself into the scene, or comparing the work in question to his own work. Moreover, he always seems to be pushing for the "next big thing," ignoring adequate comics which are interesting in their own time but don’t necessarily push the boundaries.

On the other hand, Grant Morrison is the most intriguing character in this book, and he stands up to his portrayal as a person who was influenced by comics, and has influenced comics. His personal beliefs, in the comics universe, in higher universes, in magic, and the membranes between these worlds is also mesmerizing, although a bit more bizarre. I don’t know if he’s being 100% truthful in these episodes, but they are definitely exceptional in the pantheon of comic creator stories. And the most interesting thing about Grant Morrison is his passion for superheroes, what they represent, and the possibility of fictional heroes creating the real world. It’s truly amazing, and shows in his works.

Summary: Supergods - adequate psychoanalysis of the superhero mythology, mesmerizing autobiography of Grant Morrison.

Related articles

- This Is Not a Review of Grant Morrison's 'Supergods' (joeymanley.com)

- My Thoughts On Grant Morrison's Supergods (Spiegel & Rau, 2011) (themalaysianreader.com)

- Supergods: Our World in the Age of the Superhero by Grant Morrison - review (guardian.co.uk)

11/16/11

"Mail Order Mysteries" by Kirk Demarais

Recently I've extended my diet of podcasts beyond the two staples: "The New York Times Book Review", and "This American Life." I was looking for comic-book based podcasts, but so many of the so-called reviews are either blow-by-blow recaps of the latest issue of "The Ultimate Spider-man," or blatant fanboy gushing over the cool art, that I began to despair. Then I discovered boing-boing's "Gweek" podcast. It's an excuse for Mark Frauenfelder to discover interesting nooks and crannies of comics, pop music, movies and geek pop culture in general. In "Mail Order Mysteries" Mark interviews Kirk Demarais, who has compiled a book of the ads found in comics in the '60s, '70s and '80s, paired with actual samples of the merchandise which he has tracked down over the years. As Demarais writes:

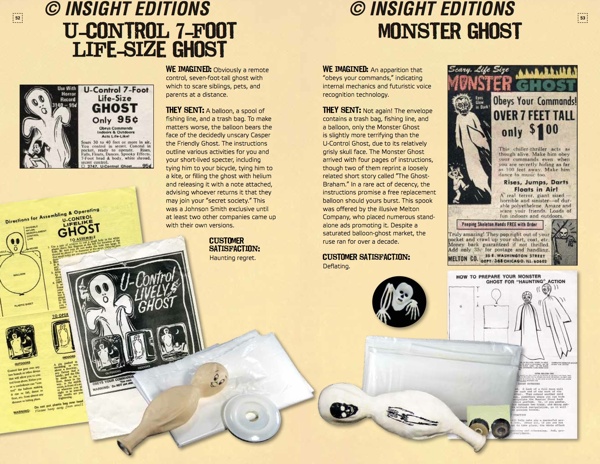

"I turned to an overcrowded page of fascinating black-and-white drawings; I was captivated It was an ink-smudged window into an unfamiliar realm where gorilla masks peacefully lived among hovercrafts and ventriloquist dummies. A dozen pages later an outfit called the Fun Factory featured another full-page assortment of wonders, and elsewhere in the issue I found a hundred toy soldiers for a buck, an offer for a free million dollar bank note, and an ad for something called Grit."In the interview Frauenfelder asks Demarais what the rarest of these sorts of toys might be. As I heard the question I figured it would be something like the missile-firing tank, or the rocket-firing submarine. I figured it would be something large and expensive. My mind briefly jumped back to the episode of "Get A Life" where Chris Elliot finally gets his Neptune 2000 in the mail. Not so! It turns out the the rarest mail-order toy is the remote control 7 Foot Life-size Ghost. I'm alone in the car listening to the interview on the way home from work. So, I'm surprised to hear my own voice aloud in the car. "No freakin' way!" I remember buying that ghost. I probably cut up a comic to get the coupon, and then probably put my own dollar into the envelope. I don't remember how long it took to arrive, but when you're in fifth grade anything longer than a week seems like forever. When it finally arrived I opened the package, which was suspiciously light even if it contained a ghost. It turns out the "ghost" was a white balloon, a white sheet of plastic indistinguishable from a disposable picnic tablecloth, and a small spool of fishing line. You were supposed to inflate the balloon, put it under the sheet of plastic, and use the fishing line as the remote control. I only remember trying it out on my door for about five minutes and spending maybe five more trying to get my sisters to walk past the ghost and be scared. After that the balloon probably popped turning into just so much trash. So, here's this guy on the podcast talking about trying to buy a vintage 7 Foot Life-size Ghost. He found one on e-Bay, but other people were bidding it up. Demarais is an associate college professor, and it happened that the auction ended during one of his lectures. At the end of the auction he had to put the class on hold while he attempted to snipe the Ghost. Unfortunately he lost the auction, but fortunately the winning bidder allowed Demarais to take photos of it for the book. How much was the winning bid? Over $300! "No freakin' way!" I said again. But, I knew it was obvious. The Ghost was such a piece of crap that any that were sold most likely ended up in the garbage before the next dawn. That's why crazy people end up spending over $300 on a piece of utter ephemera. Meanwhile, the interview intrigued me enough that I could be convinced to drop the $20 for the book "Mail Order Mysteries" just because of the memories it might bring.

Related articles

- Super Magician Comics Vol 4 No. 4 - August 1945 (comicsbin.blogspot.com)

- Air Cars to X-Ray Spex: An Interview with Kirk Demarais (wired.com)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)