In "Breaking Free

From there, the summary of the plot as Wikipedia puts it:

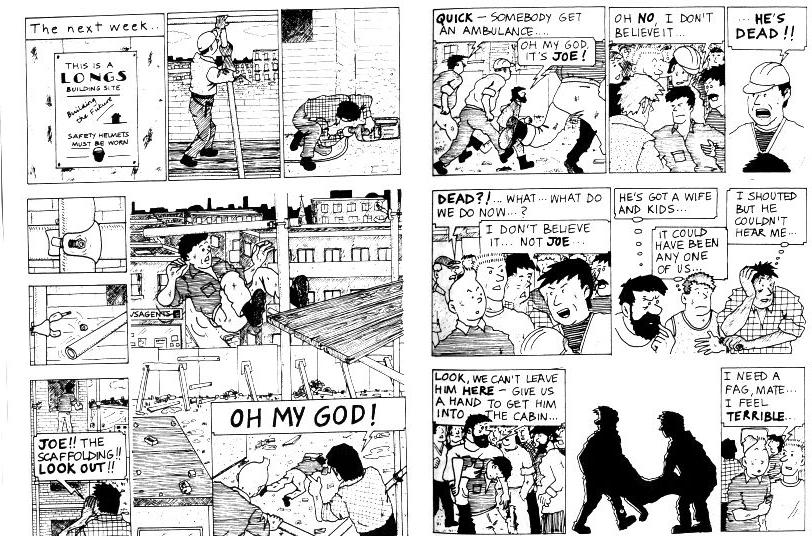

The workers become increasingly militant, turning to violent tactics and eventually firebombing the original building site. The strike begins to spread to other areas of the country without any official union involvement. Panicked, the UK government deals with strikers with increasing violence and repression, demonstrations turn into riots, and the Captain is arrested on false charges of conspiracy. As the story closes, there is a demonstration of half a million people in the town in which the events of the book unfold, several people have brought rifles and references are made to "strike committees" taking power in other areas of the country, the army being sent into Liverpool to "restore order," and similar unrest taking place around the world. The last page features the Captain, Tintin and the Captain's Wife Mary in silhouette. Tintin holds an assault rifle above his head, while the others raise their fists. Below is written: "This Is Not The End / Only the beginning…"Obviously, this isn't the sort of story Hergé would have written, let alone agreed to associate with Tintin. Much of the art looks like it's made by tracing actual Tintin characters into the story. The first page is pretty shaky, and the drawing doesn't improve over the next 170 pages, but it's a dedicated effort. In true anarchist/collective mentality no single artist gets credit for the work, mentioning only that the book is done by "Attack! International." Contrasting this book with the Hergé Tintin stories where one or two characters save the day, the point of this story is that only through the solidarity of the workers can change be effected.

When I first found this comic in 1989 or 1990 I read it in one standing in the aisle at Powell's bookstore. Although it reads quickly, at 170 pages I must have stood there for about an hour. I'm always interested to see comic icons re-purposed and reinvented, and this was only a couple years after Frank Miller had invigorated Batman with his miniseries "The Dark Knight Returns

The copy I have is from 1989 and cost 2 UK pounds. Since then it seems that there's been a reissue with a new cover. You can also read the entire book (minus the cover) online. One thing's for sure, Spielberg isn't going to turn this Tintin story into a movie.