The DC Wiki has a good synopsis of the story:

"Batman breaks into Gotham Prison to question Ra’s al Ghul about the killing of Talia. Ra’s admits that he is responsible for the incident, then turns a gun on himself, and throws the gun towards Batman before he falls. Guards assume Batman is responsible for another murder, and the Caped Crusader must fight his way out past guards and convicts."

Read 'em? Good. Now let me interrupt to skip ahead thirty years.

At the Stumptown 2011 panel on teaching comics Diana Schutz from Dark Horse, and Brian Michael Bendis discussed the way they teach comics literacy and creation, often comparing comics to movies. Bendis offered a number of books he uses as references when he's teaching, including Ivan Brunetti's "Cartooning: Practice and Philosophy

Interestingly enough, Bendis also mentioned that the editors at Marvel are tending toward dropping thought balloons. This would align with the suggestions from Brunetti and Mamet, but also seems to truncate a dimension that's fairly prevalent in comics, especially Marvel superhero comics: the internal narrative. Think of an early Spider-man fight that didn't include Peter's personal worries about Aunt May, money, and whether Mary Jane was interested in him or not.

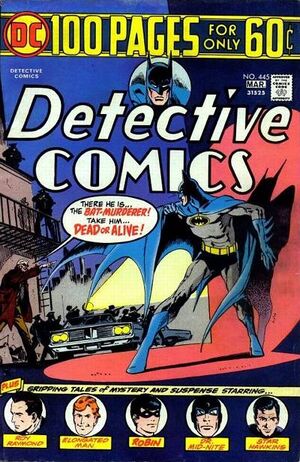

So, as a personal experiment, I decided to doctor up a random couple of pages and compare whether it was "better" with, or without the external narrative and the internal thought balloons. The preceding pages are the result. Compare the altered pages with the originally published art as it appeared in Detective #445:

First, let's look at the narrative. Most of the information is already captured in the images: we don't need to know that it took an instant to climb the wall, or that a spotlight narrowly misses exposing Batman's break-in. That's clearly shown in the images. The only part of the narrative which isn't completely shown in the images on the first page is that Batman is considered the "world's greatest escape-artist," which seems irrelevant and overblown compared to the subtle action on the page.

On the second page the narrative gives us two more bits of information: first, that it has taken the Batman a while to successfully penetrate to Ra's Al Ghul's cell, and second that it is Ra's in the cell. Again, I found these bits of information irrelevant to the story. From frame 3 to frame 5 I can see that Batman changed into a prison guard's uniform. That must've taken a bit of time, so why restate it in the narrative?

When I was a kid I regularly skipped the narrative boxes. In my mind they mostly served to obscure the artwork, only occasionally producing an interesting footnote or editor's note. This little experiment shows my inner child was right on the money for narrative in comics.

So, can the same be said for the thought balloons? Is Batman's internal dialogue also irrelevant?

In this sequence the Batman has only four explicit thoughts. Of the four, two are spent explaining action we can already see on the page: the searchlight sweeping toward him, and the guards' approach. Two others, however, provide some insight into Batman's character. First, that he was a consultant on the prison's design, and he's exploiting that information to break in. Second, even the Batman worries about his physical limitations. These internal thoughts expose the humanity behind the mask, and help the reader identify more closely with the man who's trying to clear his name in a frame-up for murder.

As this site mentions, "thought balloons have fallen out of fashion in recent years in preference for narrative captions." So, this is just moving the thoughts from the position within the image, to one that's aligned along the top or bottom of the image. Personally, I'd rather have relevant thoughts integrated into the image (as a thought balloon), rather than an internal dialogue that's distanced from the character, a la Prince Valiant for example.

Bottom line? It's likely that the average comic from the '70s, and maybe from any time period, will have redundant captions that echo the action in the image. For the most part, it probably makes the comic stronger to eschew these narrative crutches, and to follow the ideals of Brunetti and Mamet. On the other hand, I think that losing thought balloons, or relegating them to the edges of the frame in a narrative box, cuts off one of my favorite aspects of comics: the ability to show the internal dialogue of the character in an immediate way.

Incidentally, if you want to read the full arc of this Batman / R'as al Ghul story, the site Pulp & Dagger says it was collected in a 1981 digest called the "Best of DC digest #9."